Every 50 years, flowers and fear bloom in the forests of the Mizo hills.

It’s how the state of Mizoram was born, and carved out by a famine.

PART I: A prophetic Chinese proverb, and a curious letter from the east.

In the late 19th century, Kew Gardens in London received an unusual letter from John Mitford Atkinson, a British medical officer stationed in Hong Kong. In the letter, Atkinson described a curious pattern that aligned with an ancient Chinese proverb: the flowering of bamboo, he noted, seemed to herald disaster. The officer observed that bamboo had flowered in 1894, 1896, and 1898 — each time, coinciding with devastating outbreaks of bubonic plague.

It was during one of these epidemics that Alexandre Yersin, a French bacteriologist, discovered the bacillus responsible for the plague and its transmission by fleas on rats. John’s observations, combined with Yersin’s findings, lent credence to the ancient proverb, or rather, prophecy. The mass flowering of bamboo led to an abundance of seeds, which caused a boom in the rat population, inadvertently setting the stage for the spread of plague.

About 2000 kilometers west of Hong Kong, there is a place where a similar proverb prevails-"When the bamboo flowers, famine, death and destruction will soon follow." This place belong to the Mizo people who occupy today’s hill state of Mizoram in north-east India.

About 57% of the geographical area of Mizoram is under Bamboo cover (According to Government of Mizoram). And in these dense forests, a silent clock ticks away—a natural cycle understood only by those who have lived closely with the forest for generations. It doesn’t measure time in days or years but in the fifty-year intervals when the bamboo, as ancient as the hills, bursts into bloom. The Mizo people, deeply attuned to the land's rhythms, have long known what this rare bloom signals: the onset of a famine.

PART II: Elders of the forest

The Mizo elders held a profound knowledge that was quite a mystery to the colonial administrators. Their intimate bond with the land endowed them with an almost uncanny precision in predicting the next famine.

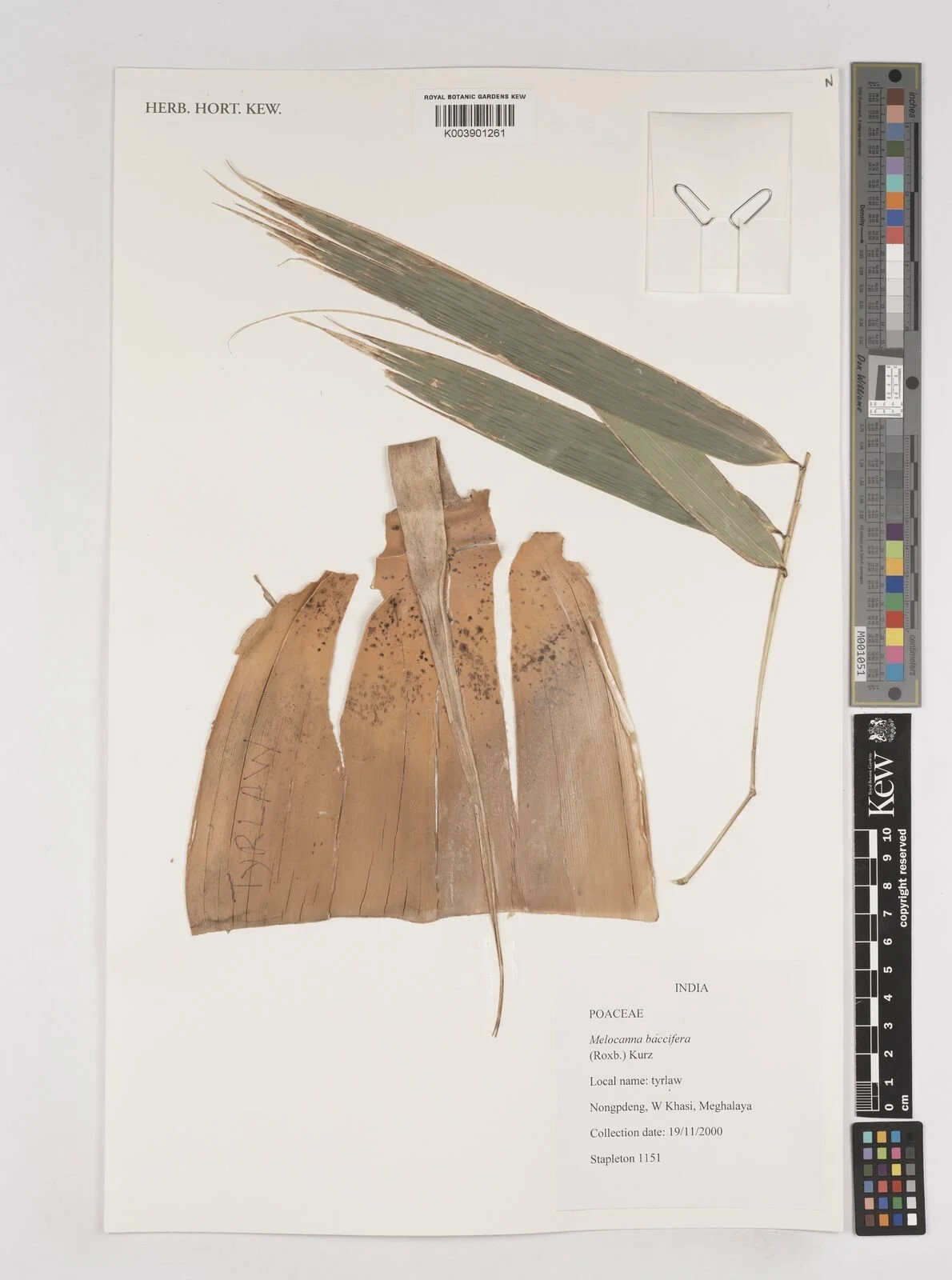

The answer lay in their knowledge of bamboo, the towering grass that covered the region like a thick blanket. Over generations, the Mizos had witnessed the bamboo's mysterious cycles of flowering and had come to understand its ominous significance. They had identified two distinct varieties of bamboo — one they called 'Mau,' the other 'Thing.' Little did the colonial botanists know that 'Mau' was what would later be classified as Melocanna baccifera, and 'Thing' would be Bambusa tulda.

These two bamboo species followed a strict natural rhythm, flowering and producing seeds every 30 and 50 years, respectively. The Mizos had learned that when the Mau bamboo bloomed, a plague of rats would follow, feasting on the abundant seeds. As the rats multiplied, they would soon turn to the Mizo's food stores, devouring everything in sight. The result was a devastating famine, known as 'Mautam.' Likewise, the flowering of the Thing bamboo brought its own cycle of destruction, leading to the famine called 'Thingtam.'

Mautam: 1861-62

〰️

Thingtam: 1881-82

〰️

Mautam: 1911-12

〰️

Thingtam: 1929-30

〰️

Mautam: 1959-60

〰️

Thingtam: 1977-78

〰️

Mautam: 2007-08

〰️

Mautam: 1861-62 〰️ Thingtam: 1881-82 〰️ Mautam: 1911-12 〰️ Thingtam: 1929-30 〰️ Mautam: 1959-60 〰️ Thingtam: 1977-78 〰️ Mautam: 2007-08 〰️

Image: A Kew Herbarium specimen of Melocanna baccifera, known as Mautak in Mizoram, the most abundant bamboo species in the state's forests.It was as if the very land itself had a heartbeat, pulsing every few decades with the same tragic rhythm. The Mizos, with their deep reverence for nature, had tuned into this heartbeat long before the Europeans ever set foot on their soil. In doing so, they not only survived the harsh cycles of famine but also left behind a legacy of knowledge that would be remembered for generations.

PART III: The forest sows, the rats reap, and the people go hungry.

Bamboo has a mysterious and unforgiving life cycle, one that scientists describe as 'gregarious.' If you have ever witnessed a bamboo flowering or seen its seeds, know that you have witnessed nothing short of a miracle. Bamboo flowers in a way that is both peculiar and unique. It waits for decades, and when it decides to bloom, it does so not just in one corner of the forest, but across vast regions, with every shoot flowering in unison.

This synchronized flowering is rare and unique to bamboo. Once a species begins this process, there’s no turning back. After flowering, each bamboo clump releases hundreds of small, mango-shaped seeds before withering away.

However, it’s the aftermath of this flowering that spells catastrophe. The seeds, scattered abundantly across the moist earth, attract hordes of rats and rodents. Nature, in its cruel wisdom, has designed these creatures to thrive on bamboo seeds, their fertility spiking as they gorge on the sudden bounty. This isn’t just local folklore. Ecologists Fabian M. Jaksic and Mauricio Lima, in their study at the Center for Advanced Studies in Ecology and Biodiversity in Chile, found a clear link between rodent outbreaks in South America and the combination of bamboo flowering and heavy rainfall—a pattern that has been noted since the 16th century.

PART IV: A state carved out by famine; the birth of Mizoram.

Post-independence, the Assam government (of which Mizoram was then a district), led by Chief Minister Bimala Prasad Chaliha, dismissed the Mizo people's warnings about an impending famine linked to bamboo flowering, labelling it as unscientific and a mere superstition. The Mizos had initially feared marginalization after merging with India post-independence, hoping for autonomy and equality. When the predicted Mautam famine struck in 1959, the government was unprepared and lacked the infrastructure to deliver relief, leading to widespread starvation and death in the Mizo hills.

In response to the 1959 famine, the Mizos formed the Mizo National Famine Front (MNFF), to coordinate relief efforts. The organization did significant work to alleviate the disaster. However, the Assam government's perceived indifference fueled a deep sense of alienation among the Mizos, leading to growing separatist sentiments. This discontent, rooted in the belief that they had little in common with the rest of India, eventually led to the transformation of the MNFF into a political party, the Mizo National Front (MNF), which began advocating for Mizo interests, submitting a statement to the Indian government on October 30, 1965.

It read:

”During the 15 years (1947-62) of close contact and association with India the Mizo people had not been able to feel at home with India or in India, nor they have been shared (sic) by India. They do not there- fore, feel, Indians. Being created a separate nation, they cannot go against the nature to cross the barriers of nationality (to become Indians). They (therefore) refuse to occupy a place with India as they con- sider it to be unworthy of their national dignity and harmful to the interest of their posterity. The only aspiration and political cry is the creation of Mizoram a free and sovereign state to govern herself, to work out her own destiny and to formulate her own foreign policy...”

On March 1, 1966, the Mizo National Front (MNF) declared Mizo independence from India, sparking a 30-year insurgency that only ended with a peace accord in 1986. Now, the MNF governs the Mizo state as a legitimate political party. Both the state and central governments are keen to avoid a repeat of past events, working to ensure the Mizos feel included within the Indian nation and preventing any resurgence of alienation.

PART V: Traditional wisdom in a modern world

The aftermath of the famine was not just physical but deeply political. The government, blinded by its belief in modern science and bureaucracy, had failed to recognize the value of the knowledge held by the local communities—knowledge that had been honed over centuries through direct experience with the land and its cycles.

The neglect and suffering fueled anger and resentment, leading to the rise of the Mizo National Front (MNF), a group that would fight for Mizoram’s independence from India. The scars of the Mautam famine left an indelible mark on the psyche of the Mizo people, a reminder of the dangers of ignoring traditional wisdom.

Today, as the world grapples with the escalating challenges of climate change, there is a growing recognition of the value of local TEK (Traditional Ecological Knowledge). The story of Mizoram’s Mautam is a powerful example of why we must listen to those who live closest to nature. These communities, with their deep understanding of ecological cycles and natural phenomena, hold insights crucial for our planet's survival. Their knowledge is not just folklore; it is a testament to the resilience and adaptability of human societies.

In a world increasingly dominated by technology and data, we must not forget the wisdom of the past. It is knowledge that, if respected, can guide us through the challenges that lie ahead.

Sources:

1. Tribals, Famine, Rats, State and the Nation, by Sejal Nag. Published By: Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 36, No. 12, 2001)

2. Curse of the Bamboo Flower, by Charlotte Rowley, kew.org

3. Bamboo - A Curse and A Blessing For Mizoram, zizira.com

4. Mautak will flower, India Environment Portal